my favorite movies of 1955:

(2) Rififi

(5) The Big Combo

favorite of 1955:

The Night of the Hunter(Robert Mitchum, Shelley Winters, Lillian Gish, Billy Chapin, Peter Graves. Directed by Charles Laughton.)The Night of the Hunter was a flop that eventually became recognized as a masterwork. Why didn’t audiences like it at first? Maybe this offbeat blend of Southern Gothic, film noir, fairy tale, and psychological horror about a religious con artist was too far ahead of its time. Also, the beginning and ending are relatively weak, so the movie might not have made a great first or last impression on people seeing it in the theater. It helps to brush those parts aside and focus on the strengths of The Night of the Hunter, which are most of the movie.

Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter is one of the greatest of all American films, but has never received the attention it deserves because of its lack of the proper trappings. Many “great movies” are by great directors, but Laughton directed only this one film, which was a critical and commercial failure. … And many great movies are realistic, but The Night of the Hunter is an expressionistic oddity, telling its chilling story through visual fantasy. … Yet what a compelling, frightening and beautiful film it is! And how well it has survived its period. Many films from the mid-1950s, even the good ones, seem somewhat dated now, but by setting his story in an invented movie world outside conventional realism, Laughton gave it a timelessness.

The movie focuses on two children who need to protect themselves when grown-ups won’t. I love the moment when one of the adults finally appreciates the kids’ power and says this to one of them (with an unfortunately dated use of “man” to mean humanity — the movie is set in the Great Depression and has a lot of old-fashioned language):

Stream The Night of the Hunter on YouTube (free with ads), Tubi (free with ads), Kanopy, or these sites.

2nd favorite of 1955:

[French: Du Rififi Chez les Hommes] (Jean Servais, Carl Möhner, Robert Manuel, Jules Dassin [as “Perlo Vita”], Magali Noël. Directed by Dassin.)After the director Jules Dassin was blacklisted by Hollywood, he moved abroad and made this French movie, Rififi, which builds on the heist movie genre created by The Asphalt Jungle (one of my favorite movies of 1950). This Criterion essay elaborates:

John Huston had established the rules of the caper film with … The Asphalt Jungle; Dassin put greater emphasis on the process. The gang spends much time studiously casing the [jewelry store] and the apartment upstairs, then doing meticulous research on the store’s hypersensitive alarm system. The actual burglary … is an unforgettable half-hour tour de force. Employing an umbrella and a fire extinguisher among its tools, the heist involves commando-raid timing and brain-surgery precision. [The thieves] exhibit the wordless teamwork of astronauts in deep space. The only thing to break the silence is the musique concrète of clinking tools, a humming drill, gently falling plaster, the quickly muffled alarm, and occasional footsteps in the street.

Ebert’s review adds atmosphere:

Dassin was a particular master of shooting on city locations. … In “Rififi,” Dassin finds everyday locales: Nightclubs, bistros, a construction site, investing them with a grey reality. Just before the heist begins, there is a scene all the more lovely because it is unnecessary, in which nightclub musicians warm up and gradually slide into collaboration. There’s a real sense of Montmartre in the 1950s.

Rififi was controversial — Wikipedia tells us:

The film was banned in some countries due to its heist scene, referred to by the Los Angeles Times reviewer as a “master class in breaking and entering as well as filmmaking.” The Mexican interior ministry banned the film because of a series of burglaries mimicking its heist scene. Rififi was banned in Finland in 1955 and released in severely cut form in 1959 with an additional tax because of its content. In answer to critics who saw the film as an educational process that taught people how to commit burglary, Dassin claimed the film showed how difficult it was to actually carry out a crime.

After we’ve gone through the possibly amoral experience of empathizing with the thieves and enjoying the half-hour heist, one thief’s wife brings a conscience to the movie when she lays this devastating point on him:

Rififi is often hard to find streaming, but you can stream it for free on Fawesome, and it will be live-streamed on Plex (free with ads) on March 1, 2025, at 9:04 p.m. Eastern. Aside from that, I recommend the Criterion blu-ray (or DVD). You might be able to get a better price with the Barnes & Noble 50% off sale on all Criterion movies, which usually happens throughout July and November. (Amazon often lowers its prices during those sales.)

3rd favorite of 1955:

(Jane Wyman, Rock Hudson, Agnes Moorehead. Directed by Douglas Sirk.)

A male arborist (Rock Hudson) and an older, more affluent widow (Jane Wyman) enter a relationship that draws scorn from their community. This movie isn’t perfect; some of the acting is wooden, including Hudson, who feels dated in his self-conscious attempt to project earthily masculine attractiveness. Wyman is the standout, with her subtle portrayal of the conflicted woman.

All That Heaven Allows was directed in a lushly expressionistic style by Douglas Sirk. (For more about his approach, see my post about Imitation of Life, one of my favorite movies of 1959.) The commentary on the Criterion blu-ray/DVD often notes how the Sirkian attention to visual details (color, clothing, etc.) beautifully underscores the story and characters.

There’s no question that All That Heaven Allows is a melodrama that was specifically marketed at women, but anyone should be able to appreciate this movie. I was struck by one scene which reminded me, oddly enough, of a moment in The Terminator (one of my favorite movies of 1984) where a young person in a dystopian future stares at a fire in a hollowed-out TV. In All That Heaven Allows, the woman is alone in her staid, upper-middle-class home with a new TV set that’s been pitched to her as an exciting way to improve her life in the 1950s, and the TV screen is reflecting her fireplace as a call-back to an earlier scene involving the couple, when the man’s fireplace burned in his more rustic home.

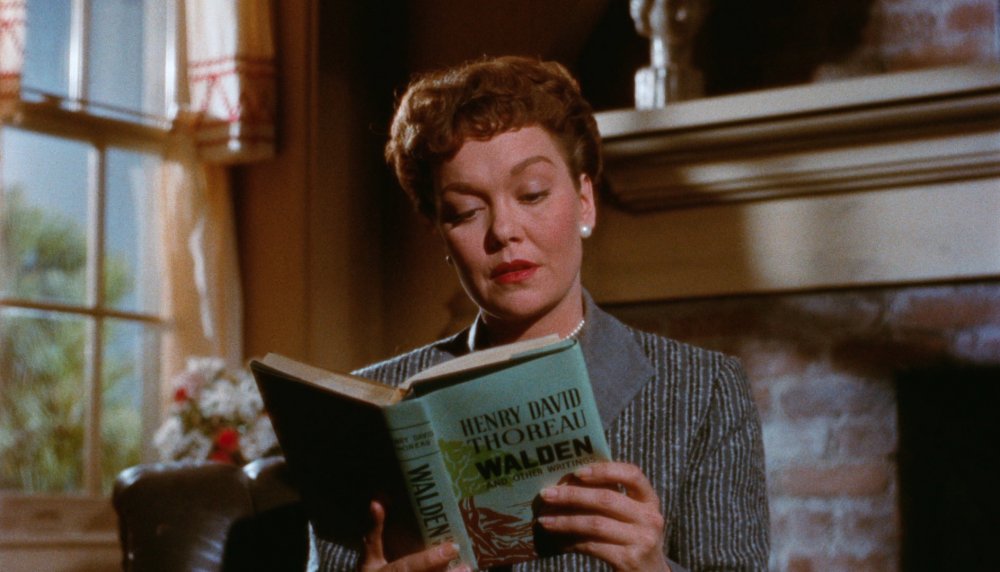

Earlier in the movie, Jane Wyman reads out loud from Henry David Thoreau’s Walden:

Stream All That Heaven Allows on Amazon Prime (leaving after June 2024).

4th favorite of 1955:

Smiles of a Summer Night[Swedish: Sommarnattens Leende] (Gunnar Björnstrand, Eva Dahlbeck, Ulla Jacobsson, Björn Bjelfvenstam, Jarl Kulle, Margit Carlqvist, Harriet Andersson, Åke Fridell, Naima Wifstrand. Directed by Ingmar Bergman.)Ingmar Bergman made Smiles of a Summer Night at the end of a suicidally depressive period in his life, and this movie became his big commercial breakthrough. It’s unusually comedic and light for Bergman, but it’s heavier and darker than most comedies.

A Criterion essay on this movie says: “Consider now what Bergman views as one of the greatest goods and one of the greatest evils. That perhaps supreme good is what he calls contact; the name of the fate worse than death is humiliation. … What happens when attempted contact fails: humiliation for one or both parties.” While watching Smiles of a Summer Night, notice when and how the various characters are humiliated.

You can stream Smiles of a Summer Night on the Criterion Channel (with bonus features). If you want to own it, you could buy Criterion’s set of 39 Bergman movies in the Barnes & Noble 50% off sale on all Criterion movies, which happens every November and July. (Amazon often lowers prices during those sales too.) I have the set — an amazing deal at less than $4 per blu-ray.

5th favorite of 1955:

The Big Combo(Cornel Wilde, Richard Conte, Jean Wallace, Brian Donlevy, Helen Walker, Lee Van Cleef, Earl Holliman. Directed by Joseph H. Lewis.)This movie is in the public domain, so you can watch the whole thing free on YouTube (or stream it on Kanopy or one of these other sites):

Not many movies from the ’40s and ’50s live up to the stereotype of a film noir that developed later on — you know, the black and white detective movie with a sultry jazz soundtrack and everything covered in shadows. But The Big Combo does. Don’t watch this movie for the story; watch it for the style, the music, the lighting (it would feel more appropriate to say “darkening”) — all quintessential noir.

This shot from The Big Combo is considered one of the most iconic images in film noir, by the revered cinematographer John Alton:

This quote is from a chilling scene that starts 55 minutes into the movie, where Cornel Wilde and Jean Wallace (who were married in real life) play a detective confronting the villain’s mistress at a classical concert:

It’s hard to believe that a shot of implied but clear sexual activity (at the end of the scene that begins at 27:15) was allowed in this movie in 1955. The director, Lewis, has explained that the censors confronted him about that scene, but when Lewis asked what the problem was (as if he didn’t know), the censors were too bashful to get specific, so they dropped the issue and left it in the movie!

Click here for the full list of my favorite movie(s) of each year from 1920 to 2020.

Comments

Post a Comment

Thanks for submitting a comment on my movie blog! 🎬 Your comment won’t show up here right away. 😐 To make sure your comment gets seen, I recommend sharing this post on social media and saying whatever you feel like! 🤓