14 thoughts on Ghost World (2001)

Now that I’ve chosen Ghost World as my favorite movie of 2001, here are more thoughts on the movie, which you can stream on Amazon Prime (leaving after July 2025), Tubi (free with ads), Kanopy, or these sites.

SPOILER ALERT: These notes discuss the plot of Ghost World including the ending.

If you copy and paste anything from these original notes by me, please credit me AND link to this post (or the blog’s homepage). To emphasize what it says at the bottom of every post on this website: Copyright © 2022-2024 by John Althouse Cohen. All rights reserved.

(1) The world of Ghost World is one of mass-produced tastes, narrowed visions, and dulled minds. We can see a spark of individuality only in the few people who haven’t let themselves be beaten down by the monoculture, which somehow dominates everything despite having no visible leaders.

(2) The opening credits set the tone, with Enid (Thora Birch) dancing at home while people in other buildings look stultified and don’t seem to hear the music: a quirky, upbeat Indian rock song from 1965 called “Jaan Pehechan Ho.” Enid mimics the dancer in the music video, wiggling her hands in an unusual position (palms facing herself), while her face is barely visible under her black hair.

This choice of music is significant in a few ways. It’s from a culture outside the US, hinting that Enid stands apart from the mainstream culture of her American hometown. The music energetically goes back and forth between “parallel” major and minor keys. (Parallel major and minor keys are, for instance, C major and C minor; the keys share the same first note or “root,” but some of the other notes are different.) Major is usually associated with happiness, and minor with sadness, but the way this song shifts between them so rapidly seems more expressive of confusion or indecision than any clear emotion. By playing this manic song while everyone other than Enid seems to be lethargic, the movie foreshadows scenes where her energy level is above everyone else’s, e.g. when she and Seymour (Steve Buscemi) go to a sex shop. The subtext is that Enid is alive in a sense that other people around her aren’t; this can be exciting for her, but also painful.

(3) Watching Ghost World puts me in a similar mindset as when I watch One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (my favorite movie of 1975). They each follow a wild and foolish but lovable misfit (Thora Birch, Jack Nicholson) who has an urge to rebel against the stifling environment they find themselves in, and to connect with similarly disaffected folks. In Cuckoo’s Nest, Nicholson is in disbelief when he hears that most patients in the mental institution are there voluntarily, not committed. In Ghost World, Seymour seems bewildered that most people around him are gladly acquiescing to the dominant culture: while he’s driving away from a bar where an older ragtime guitarist he loves was ignored by the other customers, who cared more about a younger hard rock band that crassly mimics the blues by singing about “pickin’ cotton all day long,” he vents to Enid: “It’s simple for everybody else — you give ’em a Big Mac and a pair of Nikes and they’re happy! I just — I can’t relate to 99% of humanity!” (Other parallels between the two movies are left as an exercise for the reader.)

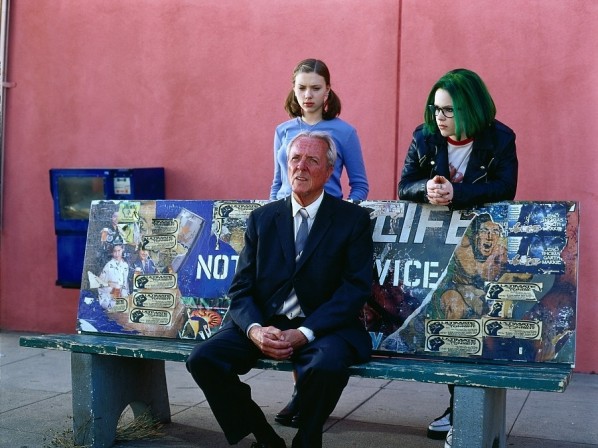

(4) In the scene where Enid and her best friend from high school, Rebecca or “Becky” (Scarlett Johannson), look at apartment listings at a diner, the groundwork is laid for Enid and Rebecca to drift apart from each other: Rebecca says they should try to convince people they’re “these totally rich yuppies.” Enid scoffs: “What are you talking about?” Rebecca explains: “That’s who people want to rent to, so all we have to do is buy, like, semi-expensive outfits and act like it’s no big deal.” The scene ends with Rebecca unconvincingly saying, “It’ll be really fun,” while Enid stares at her with a skeptical smirk. We immediately cut to Enid at home, playing punk rock on her stereo while dying her hair green. Enid isn’t going to go along with Rebecca’s plan of pretending to be “yuppies.” Maybe she’s worried if they start doing that ironically, one day they won’t be pretending anymore.

(5) The way the girls clash over whether they should pose as “rich yuppies” makes it seem like Ghost World is going to be about class divides. But no, this isn’t a movie about the rich and poor; everyone in town seems to be more or less middle-class. In the world of Ghost World, people’s lives are limited not so much by a lack of material resources as by their own lack of taste and alertness and curiosity.

(6) Still, Ghost World does get political. There’s the student who reliably delights the art teacher by making sculptures as statements about abortion and feminism. When she presents a tampon in a teacup as her artwork, the teacher enthusiastically puts words in the student’s mouth, praising her for “this shocking image of repressed femininity,” and holding it up as an example of how important it is to not be “afraid to use controversial imagery.” When Enid later tries to follow that advice, her art is canceled for being racially inflammatory. Their location is unspecified and is supposed to feel like “Anytown, USA,” but the progressive tone of the art class suggests they’re in a blue state. Enid and Rebecca seem to relish being politically incorrect: after a redneck customer in the convenience store mocks the owner in a homophobic and xenophobic way, the girls are giddy and Enid says: “That guy rules!” When Rebecca thinks she sees an apartment listing that looks good, she’s disappointed when she notices that they’d have to live with a “feminist and her two cats.” But Enid and Rebecca don’t seem like conservative Republicans; more likely, they’re politically apathetic. Seymour seems like someone who begrudgingly votes for Democrats while being cynical about politics. His most political commentary is when Enid asks why he collects old memorabilia from the chicken company he works for, whose racist mascot was replaced/whitewashed with stock cartoons of smiling white people. “I suppose things are better now,” he says. “People still hate each other, but they just know how to hide it better.”

(7) Illeana Douglas is perfect as the art teacher, Roberta. At first we think we have her pegged: a caricature of an oh-so-sensitive, hippy-dippy liberal. She introduces herself by playing her own short film (Mirror, Father, Mirror), an unintentional parody of art-house pretension, juxtaposing ominous film noir shots with a doll being dismembered — which, she earnestly confides to the class, “says so much about who I am, and what it feels like to inhabit my specific skin.”

But our view of the teacher changes when Enid brings a painting of the chicken restaurant’s racist former mascot to class. The teacher gives Enid a chance to explain, but she isn’t as eloquent as she could be. Other students object (“it’s totally offensive”). Then there’s a tense lull in the classroom when the teacher finally says: “I don’t know what to say … [awkward pause] … I think it’s a remarkable achievement.”

(8) So the teacher sees promise in Enid, and later says she “took the liberty” of applying for an art school scholarship on Enid’s behalf. The teacher is clearly genuine about helping Enid — “this could be a really great thing for you” — but her language is revealing: “took the liberty,” as if Enid’s freedom is being taken away from her by even the most well-meaning people. The teacher defends Enid when her painting causes an uproar at the student art exhibit, and it’s Enid’s fault she isn’t there to explain herself because she’s busy hooking up with Seymour. Enid’s apathy sets off a chain reaction: the censors take down her artwork, forcing the teacher to give Enid “a non-passing grade” (a nice detail: the teacher uses that delicate euphemism because she can’t bring herself to say anything as judgmental as “failing”), which disqualifies Enid from the art school scholarship. There’s no reason any of that should spell doom for Enid — she doesn’t seem to be struggling economically, so she probably doesn’t need the scholarship. Her problem is deeper than one missed opportunity: it’s a bad omen, a sign that the world will never accept her attitude.

(9) Not showing up to explain her art at the exhibit is one of many examples of how people in this movie (especially Enid) keep failing to explain themselves — so often that the movie could have been called I Can’t Explain:

After the girls mock Seymour from a distance and then meet him, Enid reveals to Rebecca that she’s starting to warm up to him: “I kind of like him. He’s the exact opposite of everything I really hate. In a way, he’s such a clueless dork, he’s almost kind of cool.” When Rebecca retorts, “That guy is many things, but he’s definitely not cool,” Enid struggles to respond and ends up saying: “Forget it, I can’t explain it.”

- Enid doesn’t really explain her earlier art projects; when asked why she chose to draw Don Knotts, she simply says, “I like Don Knotts” — not that he represents or expresses anything.

- At the school dance early in the movie, Enid tells Rebecca it’s “totally depressing” that they’ll “never see Dennis again.” (Dennis is a dorky loner who, sure enough, is never seen again.) Enid gives no explanation when Rebecca disagrees — foreshadowing how those two will later clash over a socially awkward man.

- Enid doesn’t explain her contempt for her dad’s girlfriend, Maxine (Teri Garr, in a sadly uncredited role), or why she brushes off her dad (Bob Balaban) when he relays Maxine’s offer to get an unexpectedly good job for Enid.

- Enid puts off explaining to Rebecca how she feels about living together.

- Enid tells Seymour at the hospital (after she ghosted him, fought with Rebecca, and quit her job): “I know I’m a total disappointment to everyone … and there is just no way to explain how I feel. I guess I just have to figure myself out.”

- The movie ends with Enid getting on the same bus she saw the old man (Charles C. Stevenson Jr.) get on, after he seemed to have no explanation for waiting for a bus that Enid said was discontinued years ago. Enid tells the man, “You’re the only person in this world who I can count on, because I know no matter what, you’ll always be here.” He says she’s wrong, and adds enigmatically: “I’m leaving town.” The bus has no explanation for showing up; it doesn’t even have a label (see #12).

- Seymour describes what he hates (the radio host’s “voice is so hateful!”) but he never explains his main obsession in life: music. When Enid asks him to list his top 5 interests (to help her find a date for him), he starts listing music genres (“traditional jazz …”). She suggests just saying “music” so he can list 4 more interests … and he’s stumped. But we don’t find out why music is so important to him that it occupies all 5 slots. There’s no backstory about some revelatory experience he had as a kid. He doesn’t talk about passions; he talks about classifications, as if he what he really wants is a sense of intellectual mastery (e.g. correcting the woman in the bar who mentions the live “blues” guitarist — actually, it would more properly be referred to as “ragtime,” he tells her, when she just wants to get up and dance). There’s no softly lit closeup designed to give us magical feelings about how Seymour and Enid have connected through music. The movie smartly plays it straight, leaving their feelings about it open-ended, so we can mentally fill in the details with our own feelings and experiences.

- Seymour doesn’t have much of an explanation for being interested in his girlfriend, Dana (Stacey Travis), beyond material things: she picks out clothing for him, they go antique shopping. He’s going with the flow and resigning himself to a lackluster, mainstream existence.

(10) In addition to “I can’t explain,” another theme is: “I can’t connect.” No connection between any two characters seems both strong and enduring. Enid’s connections with Rebecca, Seymour, and the art teacher are meaningful … but transitory. The teacher’s last moment with Enid goes from warm to cold: she starts out conciliatory toward Enid … but then turns away to attend to a student whose face is covered because he’s being used for an art project. Enid makes peace with Rebecca and Seymour in some of the most tender scenes of the movie … but she ultimately drifts away from them. The movie leaves open the possibility of a sequel in which Enid could form a more lasting bond with either Rebecca or Seymour … but that’s not this movie. Meanwhile, Rebecca and Seymour never connect on any level. (Rebecca dryly tells Enid that Seymour “should totally just kill himself.” Later, Rebecca becomes more and more exasperated at how important this middle-aged man is becoming to Enid: “God, I’m so sick of Seymour!”) Seymour sums himself up as one of the “pathetic collector losers”: “You can’t connect with other people, so you fill your life with stuff.”

(11) Despite the theme of individuals being restricted by the dominant culture surrounding them, we never see the main characters in crowds. Aside from the high school graduation at the beginning, you never see any large groups of people in Ghost World. When the characters walk around outside, the streets are eerily deserted. The sparsely populated town is a sign of alienation, of how difficult it is to connect with people.

(12) Ebert’s review describes the plot well: it doesn’t follow a “formula … and march toward … the happy ending Hollywood executives think lobotomized audiences need as an all-clear to leave the theater.” The point is not just that deviating from convention is bold and respectable, but that the specific way this movie does so is ambiguous yet full of meaning. In my post introducing Ghost World as “my favorite movie of 2001” (and the whole century, for that matter), I talk about how Enid’s contemplative experience listening to the record she bought from Seymour on repeat prepares us for even stronger tonal shifts later on. That includes the much-debated ending:

- Thora Birch and director Terry Zwigoff have radically different interpretations of what happens when Enid gets on the bus at the end. In this 2021 retrospective, Birch suggests that she doesn’t see her character going in a good direction: “Honestly, it’s a sad film, to me. I have a very dark view of where that story is leading, unfortunately.”

- But Zwigoff says: “Many interpreted it to mean Enid died by suicide. I personally thought of the ending as more positive: that she’s moving on with her life, that she had faith in herself.”

- Similarly, Illeana Douglas (the art teacher) says on a Criterion blu-ray extra: “To me, it’s a happy ending, because she does leave, so she does strike out on her own. … I think that Enid, she wrote a very slim graphic novel that 100 people read, and now she writes a blog about, I don’t know, horror films of Dario Argento.”

- Scarlett Johannson says (in the same Criterion extra): “I think these characters [Enid and Rebecca] probably don’t see each other again for a long period of time, and I think their lives really go in a totally different direction. Maybe when they both join Facebook or something, they find each other again, and Rebecca has a kid or two, and they kind of sit and just marvel at how different their lives are. It’s kind of profound I think — it’s this bittersweet ending that just finds you at this crossroads when your life is suddenly different, unfamiliar, and you’re kind of in this transitional phase, and just waiting on that bus stop, waiting on the next leg of your journey.”

- The Criterion essay on Ghost World can’t decide: “This is either the most transcendental ending of an American comedy or the most unflappably, inscrutably nihilistic. Or both.”

- Writing in the Atlantic, David Sims suggests that the ending has no exact meaning, and that’s the point: “To me, the ambiguity of Enid’s future, and her confusion over her place in the world, is the crux of those final moments.”

(13) The bus is unlabeled and Enid carries only one medium-sized bag, but we don’t need to think too realistically about whether this 18-year-old has a practical plan for what to do when she gets off the bus. She could be moving to another town, which is foreshadowed in the scene where Enid and Seymour hook up. She muses to him about two ideas for starting a new way of life. First she says: “Maybe I should just move in with you. I could do the cooking and dust your old records. …” But then she says: “You know what my #1 fantasy used to be? I used to think about one day, just not telling anyone, and going off to some random place. And I’d just … disappear. And they’d never see me again.” When they’re in bed after sex and Seymour seems to be falling for her, he wants to know if she was serious about wanting to move in with him and essentially become a housewife. What goes unspoken is that Seymour doesn’t signal any interest in her idea of leaving town. Instead, we can assume Enid does that on her own at the end of the movie. Or the bus ride could be purely metaphorical, symbolizing that she’s going to start living her life on a clean slate, and escaping from the confines of other people’s expectations.

(14) Maybe there’s no right answer to the question of what the ending means, because this isn’t the kind of movie that needs an “ending” in the sense we’re used to. This story has no real hero or villain — no one to triumph, and no one to be vanquished. Ghost World is more about the paths people are on than about any great resolution for anyone. Seymour, the lonely collector, seems for a while to be on a path of self-improvement, but we leave him on what looks like a path to nowhere. Rebecca is on a path to becoming a conventional adult, tamping down the rebellious streak she once shared with her best friend. And Enid is on a path only she can see.

Click here for my shorter post about Ghost World, and click here for the full list of my favorite movie(s) of each year from 1920 to 2020.

Looking forward to rewatching this after reading your analysis. It was a favorite in my early teens but I haven't revisited since then. /Aubrey

ReplyDelete