17 thoughts on After Hours (1985)

Here are more thoughts on Martin Scorsese’s After Hours, as a supplement to this post where I chose it as one of my favorite movies of 1985.

SPOILER ALERT: These notes discuss the plot of After Hours including the ending, so I don’t recommend reading this post unless you’ve seen the movie.

If you copy and paste anything from these original notes by me, please credit me AND link to this post. Copyright © 2022-2024 by John Althouse Cohen. All rights reserved.

(1) The anti-hero of After Hours, Paul Hackett (Griffin Dunne), starts out both bored and boring. If he were a cartoon, he’d be a stick figure with a 😐 face. He’s plain and bland, and so are the places where he spends his time. He and his environs are covered in the same drab color: he wears a beige suit, works in a beige office (as “a word processor,” back when that was a job title instead of a computer application — his job isn’t given any substance), and goes home to an apartment with beige walls, where he flips channels while lying down on a beige couch, under a picture of boring off-white buildings. We never find out any of his interests, hobbies, passions. He doesn’t even seem like someone who has “passions.” We never learn any back story for him — no past relationships, no family drama. (See #6.) We don’t know if he’s moved around a lot or always lived in New York City. It’s stunning to think how little we know about him after watching him for almost two hours.

(2) We find out more about what makes Paul’s coworker (Bronson Pinchot) tick, even though he never shows up again after Paul trains him in the first scene. On the surface, that character seems inconsequential and limited to that one scene, yet he is significant. When he confides that “I do not intend to be stuck doing this for the rest of my life,” and segues into revealing his plans to found a magazine that would allow new writers to put their work “out there” without too much “editing,” Paul immediately loses interest and his attention shifts to checking out a coworker who’s walking by. (The camera shows only her torso, cutting off her head.) Paul doesn’t seem like he has big dreams that would help him avoid being “stuck doing this” (whether that’s his job or his life overall), and he isn’t going to put himself “out there” without a lot of self-editing.

(3) Marcy (Rosanna Arquette) introduces herself to Paul in the diner after work by saying she loves the book he’s reading, Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, which she quotes off the top of her head: “This is not a book. This is a prolonged insult, a gob of spit in the face of art, a kick in the pants to truth, beauty, God.” That quote feels out of place, so why is it in this movie? You could hear it as a meta-comment on the movie, replacing “book” with “movie”: “This is not a movie…” Is After Hours mocking the idea of a movie, or those abstract ideals — beauty, truth, and art? Marcy mentions God, and the only other time God is mentioned in the movie is well after she dies, when Paul is at a low point in the street and screams at the sky: “What do you want from me?! What have I done?! I’m just a word processor!!!” That description of himself — “just a word processor” — underscores that the movie is leaving him as a blank, almost devoid of qualities (see #1).(4) Paul’s pretext for calling Marcy once he gets back home is that he’s interested in her roommate’s paperweights, and that leads to their late-night date in Marcy’s apartment and a nearby diner. The paperweights are set up as if they’re going to be a “MacGuffin”: important not because they’re intrinsically interesting or valuable, but only because the movie tells us they’re sought after, which drives the plot. But Paul satirizes the idea of a MacGuffin when he and Marcy are in her bedroom smoking “pot” (more about the “pot” later — see #14), and he suddenly demands: “Where are the paperweights?! … I wanna see a Plaster of Paris bagel and cream cheese paperweight — now cough it up!” Marcy is understandably confused: “Right now?!” Paul is insistent: “Yes, right now! … Because as we sit here chatting, there are important papers flying rampant around my apartment, because I don’t have anything to hold them down with!” (Video.) The twist is that this is the opposite of a MacGuffin: the paperweights aren’t Paul’s driving motivation — they’re his lame excuse to get out of there when Marcy storms out of the bedroom. Another irony: Paul’s apartment doesn’t seem like a place where anything’s wildly flying around. His real motivation is not to buy a paperweight, but to escape from his unadventurous life and have an experience with someone like Marcy, who seems to float freely through the world without being weighed down.

(5) Marcy’s roommate, Kiki Bridges (Linda Fiorentino), adds an edge to the movie as soon as Paul arrives downtown. She has short, dark hair and says everything in a flat, dry tone as if nothing fazes her.

After Hours tricks us into thinking it’s going to focus on some kind of friction among these three characters: Paul, Kiki, and Marcy. When Paul first gets to their apartment, he finds only Kiki, who says Marcy is away at the drug store; when Paul asks if there’s anything wrong, Kiki says, “It’s under control,” as if to be reassuring, but creating anxiety about that unknown “it.” Then Paul hears more troubling vagueness from Kiki, saying to Marcy on the phone: “Of course he’s here — you invited him! It’s your problem, Marcy, I’m not gonna tell him!” Sexual tension between Kiki and Paul builds when he takes off his shirt, which got wet when he was adding to her sculpture, and he puts on a darker shirt she gives him, while she complains that her arms are sore from working on the sculpture all day. Paul takes the hint: “Want a massage?” He lowers expectations by admitting he doesn’t know much about massage, but Kiki gives him advice: “Just make it hurt and you’re on the right track” — a hint that this movie will be about someone going through pain but getting onto a better path in life. While massaging her, Paul tries to increase the sexual tension in a conventional manner, telling her: “You have a great body.” Kiki’s response is self-assured but disconcerting: “Yes. Not a lot of scars. I mean, some women I know are covered with them, head to toe … horrible, ugly scars.” That’s blatant foreshadowing about Marcy, and maybe subtler foreshadowing about something else.

(6) There’s only one time when it seems like Paul is going to get personal about his past (see #1): he starts telling Kiki an eerie story about staying overnight in a hospital’s burn ward as a kid, and breaking a rule against keeping his blindfold on … but he never reveals what he saw, because Kiki has fallen asleep. (See above video.) Fittingly, that’s when Marcy shows up: she’ll turn out to have burns, and her story will end before it should.

(7) We get some sense of Marcy as a full human being — someone who’s been through relationships, rape, and burns. But we also have the sense that there’s more to Marcy than she reveals to Paul, as she hints when she concludes a personal monologue by saying: “Naturally I don’t like to talk about it.” We’re crushed when she kills herself before we feel that we’ve fully solved the puzzle of Marcy. She and Paul never make a genuine connection, even though Marcy seemed to have high hopes for their date: “I hope you don’t have to get up early tomorrow or anything … because I think you’re somebody I can really talk to! And tonight I feel like … I feel like I’m gonna let loose or something! I feel like something incredible is really gonna happen here! I feel sooooo excited, and I don’t know why!” After Marcy dies, Paul seems to express a level of sincerity that he never showed to her while she was alive: he breaks down in tears and repeatedly exclaims that he “didn’t even know” her. Marcy is intriguing when she enters Paul’s world, tragic when she leaves the world, and enigmatic from beginning to end.(8) This video shows many parallels between After Hours and The Wizard of Oz (one of my favorite movies of 1939), e.g. Paul in the taxi, leaving his beige apartment on the Upper East Side, a relatively staid area of Manhattan, to meet the more colorful Marcy in the more exciting Soho area = Dorothy in the tornado, which transports her from her sepia-toned ordinary life in Kansas to the colorful land of Oz. The wind takes Dorothy to Oz, and takes Paul’s cash out of the taxi, leaving him stranded in Soho. Once they’re in the more colorful place, Dorothy and Paul both “want to go home,” and they end up at home (or at work), able to look at it in a new way. The Wicked Witch of the West with her flying monkeys is analogous to Gail (Catherine O’Hara) leading the mob in After Hours. Marcy has a monologue about The Wizard of Oz, focusing on the warning from the Wicked Witch of West: “Surrender, Dorothy!” Marcy’s husband, “a movie freak,” said that phrase over and over during sex on their wedding night, which repelled Marcy so much she dumped him. (Video.)

(9) Paul goes DOWN and then UP! He leaves his Upper East Side apartment (on East 91st Street) to go DOWNtown (Soho), and near the end of the movie he goes DOWN to the bar’s basement, where June turns him into a sculpture. The two thieves find him in that seemingly inanimate (deadened) form, bring him UP into daylight, and drive him UPtown. Then he takes the elevator UP to his office, where his computer has a message as bland as he was at the beginning (see #1): “Good morning, Paul.” So the last word of the movie is his name — a very Christian name. It’s as if the taxi driver is Death, who takes him to Purgatory (being stuck in Soho), which leads to Hell (being turned into a sculpture with seemingly no escape), but he’s saved and goes up to Heaven (which is what his well-lit office will seem like after his nightmarish, transformative experience). It’s also like he’s buried and then resurrected.

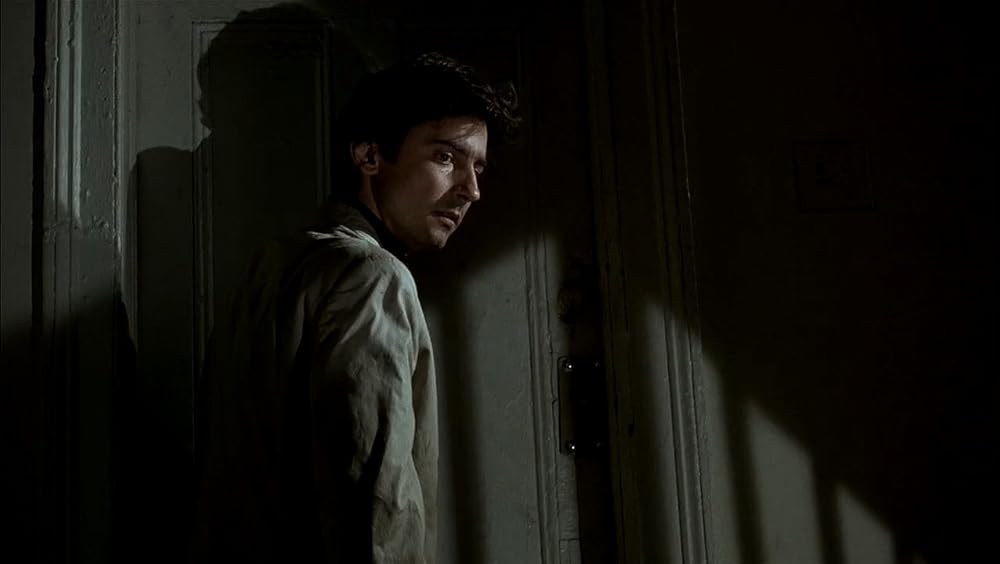

(10) Or it’s as if Paul is returning home after being through war. World War II influenced the classic film noir period starting in the early ‘40s, and After Hours has “neo-noir” elements. The focus on a wrongly accused man who feels like he has no way out of his waking nightmare is straight out of classic noir: see Out of the Past (my favorite movie of 1947) and The Wrong Man (my favorite movie of 1956). And these two shots of Paul are very noir. Film noir often uses parallel lines as if to represent prison bars trapping the characters, and puts people in confined areas and against the edges and borders of things, such as stairwells, door frames, and fire escapes:

(11) The movie often has an atmosphere of sex (Paul gets into potentially erotic situations with several women; Marcy explicitly describes having sex on her wedding night) or violence (e.g. Gail reads from a newspaper clipping that’s gotten stuck in Paul’s skin about a mob pummeling a man’s face beyond recognition; Paul later admits that if Tom the bartender had known about Paul’s desire to have sex with Tom’s girlfriend Marcy, Tom would have pummeled Paul’s face). Yet we barely see any sex or violence in the movie! Paul is physically injured only once — and it’s not intentional violence, just a mishap caused by Gail getting out of a cab without looking. Paul doesn’t do anything sexual beyond some very brief kissing and shoulder-touching, and Marcy usually recoils when he touches her.

Paul stays at a distance from sexuality: he sees mouse traps surrounding the bed of Julie, a/k/a “Miss Beehive, 1965” (Teri Garr), and he starts to undo the results of BDSM play between Kiki and her boyfriend (removing the gag from her mouth and untying the rope around her body because he mistakenly thinks she’s been robbed). The only times we see outright sex or violence are random and remote: Paul looks through an apartment building window and sees a couple having sex (with the woman on top), and later he looks through a window and sees a woman shooting a man in the chest. It’s as if Scorsese is mocking the audience, telling us: “You wanna see sex and violence when you go to the movies? OK, there’s your sex and violence! Satisfied??”

(12) When Paul creepily undresses Marcy’s corpse, he sees her leg tattoo of a skull. 💀 Then Marcy’s boyfriend, Tom the bartender (the late John Heard), gives Paul a key ring with a similar skull. 💀 Later, we see a skull 💀 on Gail’s belt buckle. All three skulls are connected to someone who seems like they could free Paul, but then turns out to be deadly — either the mob trying to catch Paul (who screams, “They’re all trying to kill me!”) or the suicidal Marcy. The skulls hint that death lurks at every turn for Paul, which is also suggested by the name of the bar where Tom and Julie (who both become instrumental to the mob) work: Terminal Bar.

(13) In a 2021 interview about the enduring appeal of After Hours, Griffin Dunne (who plays Paul and also co-produced the movie) connects it to cancel culture:

I think the increasing popularity of the movie is that it resonates with a certain paranoia that we’re all familiar with. The idea of saying the wrong thing, doing the wrong thing. Being persecuted and chased through the streets of Soho is a pretty good metaphor for how easy it is to trip up. It’s what everyone fears: to be an outcast and chased by the mob on the internet. And the movie is done, obviously, in a really funny way. I think people appreciate the persecution humor of it.(14) June (the late Verna Bloom), the mysterious woman in the bar where Paul hides (the bartender tells Paul: “Most people don’t notice her”), is the only person who truly helps Paul, and the time they spend together is the only time we see Paul genuinely passionate and caring about someone else. He might have seemed that way with other people, like Marcy … but with her, Paul seemed to be putting on a facade or going through the motions to achieve a goal for himself. You can sense Paul thinking to himself while he’s with Marcy: “Just say whatever’s appropriate, whatever you have to, to have a chance of scoring with her.” Sometimes Paul doesn’t even pretend to be nice; he keeps snapping at people (Marcy, Julie, Gail, the subway worker, the punk club bouncer). The first time he snaps is when he’s with Marcy smoking pot, which he thinks isn’t really “pot,” so it’s as if this unspecified drug alters his personality. But he’s different with June than with anyone else, and June has a different response to him than anyone else does. She asks: “Why are you doing this? You flirt with me. … You dance with me. You’re nice to me.” She repeats: “Why are you doing this?” (This starts 3 minutes into the video below.) Paul answers her in his most emotionally direct moment of the movie: “I want … to live! I just … want … to … live!” Then he repeats that verb in a hushed but urgent tone, as if he were grasping the meaning of the word for the first time: “Live!” He says this to a woman who’s noticeably older than any of the other women he’s encountered, but these two have a connection that he failed to make with anyone else in the movie. We might even wonder if he’s ever had a real connection with another person in his life until now.

(15) This man with no known passions (see #1) has been mostly going along with what whatever the world hands him: he talks with Marcy because she strikes up a conversation in the diner, asks for bagel paperweights made by Kiki because Marcy offers them, goes with Julie into her place twice without really wanting to (video of the second time), compliments Kiki’s sculpture without having much to say about it or seeming to know much about art (he says the sculpture looks like Edvard Munch’s “The Shriek,” but Kiki points out that he means “The Scream”), works on the sculpture because Kiki asks him to (giving in to her after he meekly objects that it’s her art — “how would I know what you want?”).

But in the bar with June, Paul makes his own decisions: he chooses the song in the jukebox (using the little spare change he has left), and chooses to dance with June and “bare[]” his “soul” to her. By the way, he picks the song “Is That All There Is?,” in which Peggy Lee recalls being a young child watching her house go up in flames, when she decided to “keep dancing … break out the booze and have a ball.” Paul’s song choice suggests he’s asking himself deep questions about what things in his life have value and bring fulfillment. The singer raises the possibility of suicide but rejects it: “I know what you must be saying to yourselves: If that’s the way she feels about it, why doesn’t she just end it all? Oh no, not me, I’m not ready for that final disappointment.” We can assume Paul is thinking of Marcy, and thinking of killing himself to avoid the mob.

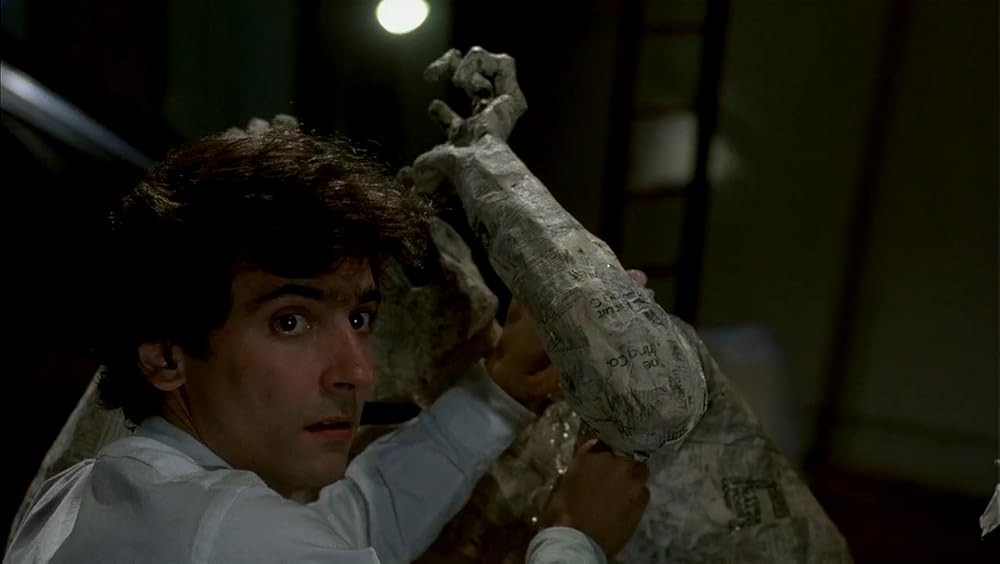

(16) The moviemakers struggled to come up with an ending. One of the rejected endings was a surreal scene in which June apparently would’ve given birth to Paul on the street! The movie seems to contain a vestige of that idea when Paul leans against June’s bosom in a vulnerable, childlike way in the basement.

At that moment, the mob bursts into the bar, and Paul needs June to protect him after he gets covered in goop, as if he were a newborn baby. This character who’s walked through most of the movie seeming to be a typical middle-class, urban, adult man has reverted to infancy. But why? So he can rethink his life and start over? The movie ends with him back at his desk where we first saw him, looking disheveled yet with a calm expression. On the surface, he’s not doing anything other than sitting there covered in dried papier-mâché paste; but inside, we can assume, he’s been profoundly changed.

(17) The last words (not counting the message on Paul’s computer screen) come from thieves (played by Cheech and Chong) who think they’ve found the sculpture they dropped when Paul ran after them, not realizing that they’ve found Paul himself, who now resembles Kiki’s sculpture. The last lines are an amusing back-and-forth:

So the movie’s last line is about the enduring value of art. But what is “art,” or what should it be? This clash between the traditional view that art should be beautiful, and the subversive idea that art has greater value when it’s “ugly,” brings back the first thing Marcy said in the movie: she loves the Henry Miller book, which proclaims that it isn’t a book, that it’s going to spit at “art” and give a kick in the pants to “beauty” and “truth.” (See #3.) After watching this strange, funny, powerful, terrifying, revelatory movie, we’re left to ask ourselves what’s really beautiful and true, how Paul’s going to live his life from now on, and how we should live ours.

Click here for a shorter post about After Hours and my other favorite movie of 1985, and click here for the full list of my favorite movie(s) of each year from 1920 to 2020.

Comments

Post a Comment

Thanks for submitting a comment on my movie blog! 🎬 Your comment won’t show up here right away. 😐 To make sure your comment gets seen, I recommend sharing this post on social media and saying whatever you feel like! 🤓